Ballard Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Family Counseling Interventions

- Enquiry

- Open Access

- Published:

Community based system dynamic as an arroyo for understanding and acting on messy bug: a case study for global mental wellness intervention in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan

Conflict and Health volume 10, Commodity number:25 (2016) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Afghanistan lacks suitable specialized mental healthcare services despite loftier prevalence of severe mental health disorders which are aggravated by the disharmonize and numerous daily stressors. Recent studies have shown that Afghans with mental affliction are not just deprived of care but are vulnerable in many other means. Innovative participatory approaches to the design of mental healthcare policies and programs are needed in such challenging context.

Methods

We employed community based system dynamics to examine interactions between multiple factors and actors to examine the problem of persistently low service utilization for people with mental affliction. Grouping model edifice sessions, designed based on a series of scripts and led by 3 facilitators, took place with NGO staff members in Mazar-I-Sharif in July 2014 and in Kabul in February 2015.

Results

We identified major feedback loops that plant a hypothesis of how system components collaborate to generate a persistently depression charge per unit of service utilization by people with mental illness. In particular, we establish that the interaction of the combined burdens of poverty and cost of handling collaborate with cultural and social stigmatizing beliefs, in the context of express clinical or other treatment support, to perpetuate low access to intendance for people with mental disorders. These findings indicate that the introduction of mental healthcare services alone volition not exist sufficient to meaningfully improve the condition of individuals with mental illness if community stigma and poverty are not addressed concurrently.

Conclusions

Our model highlights important factors that prevent persons with mental illness from accessing services. Our study demonstrates that grouping model building methods using community based system dynamics tin provide an effective tool to elicit a common vision on a circuitous problem and place shared potential strategies for intervention in a evolution and global wellness context. Its strength and originality is the leadership part played by the actors embedded inside the organisation in describing the complex problem and suggesting interventions.

Background

A recent report has shown that the global burden of mental illness has been systematically underestimated. Revised estimates show that mental disease accounts for 32 · 4 % of years lived with disability (YLDs), ranking mental illness first in terms of YLDs [1]. Despite a growing body of empirical evidence showing the considerable personal and socioeconomic affect of this brunt, existing treatment options for persons with mental affliction are express [2]. It becomes increasingly clear that is possible to develop mental health treatment programmes in depression income settings. Some NGOs take developed programs to address the mental health needs of populations in post-emergency settings such as the NGO HealthNet TPO in Afghanistan, Burundi or International Assistance Mission in Afghanistan [iii, 4]. In the province of Aceh in Indonesia, in the post tsunami period, the Ministry of Health and the Globe Health System prepare upwardly a customs-based mental wellness system integrating mental health services within main healthcare facilities, with secondary mental care available at the commune full general hospitals and third and specialized care provided at the provincial general hospitals level [3]. More by and large, the the World Wellness System (WHO) Mental Wellness Gap Action Plan (mhGAP) provide guidelines for the provision of drugs and psychosocial interventions and has informed several programs aiming primarily at integrating mental health into primary care in Low and Heart Income Countries (LMICs) [v–7]. Many other innovative initiatives such as the Plan for Improving Mental wellness care (Prime) or Africa Focus on Intervention Research for Mental health (AFFIRM) and Emerging Mental health systems in low and middle-income countries (EMERALD) have been generated bear witness on the implementation, capacity development and scaling up of mental health packages aiming at narrowing the treatment gap for mental disorders [8–10].

Notwithstanding the accomplish of these programs remains limited and many persons with mental illness (PMI) remain in need of mental healthcare services. Complex and interacting supply-side barriers of resource availability, costs of treatment, and logistical challenges to sustaining services, equally well every bit demand side factors such as out-of-pocket expenditures, long term chronic needs and social factors such as stigma around mental illness, acceptability of the setting in which handling is delivered, and lack of family participation in treatment and sensitization efforts take been shown to be major obstacles to widespread access to mental health services [11–17]. In public wellness these circuitous and seemingly intractable challenges are variously referred to every bit "wicked problems" [18, 19] or "messy problems" [20]. Addressing such barriers in low-income settings would require an integrated arroyo that involves people with mental illness themselves, their families and communities, likewise as building local capacity in existing healthcare facilities [thirteen]. Another perspective argues that dominant approaches to promoting wellness fail to business relationship for the diverseness of the "Long Tail" of vulnerable populations – diverse social groups with specific socioeconomic characteristics that have various exposure to primal wellness risks, resulting in a failure to attain the most marginalized [21], among whom the brunt of morbidity and mortality is greatest [22–25]. From both perspectives, the challenge often comes downward to the inadequacy of conventional analytic and planning tools to capture the complication of problems operating at multiple levels and with diverse stakeholder perspectives and contexts. The broad framework of "participation" in global wellness and evolution efforts has been variously embraced [26, 27] and critiqued [28, 29] as a solution to engaging with diverse local needs. Yet there is little uptake of approaches to designing policies and programs that engage with complexity, respond to the needs and promote the capabilities of the most vulnerable [30], and provide concrete steps for action.

Mental healthcare in countries in conflict represents a particularly 'messy' problem that, despite meaning discussion amid scholars and international evolution actors [31], has not been prioritized to develop widespread, constructive and well-funded intervention, particularly in low income countries and delicate contexts [32]. Limited availability of information in low income countries [33–35], broad variation in social and cultural definitions and interpretations of mental disorder [36, 37], and limited evidence about the efficacy of intervention approaches [38, 39] all pose barriers to progress.

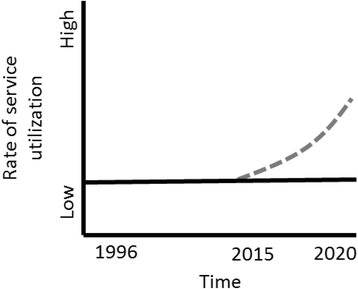

In Afghanistan recent studies have reported loftier prevalence of diverse mental health disorders linked to the conflict and various psychosocial stressors associated with poverty, loss of employment, drug abuse and traumatizing events [40–42]. Despite important initiatives, the current lack of mental healthcare services is a considerable claiming. To date, Transitional islamic state of afghanistan lacks widespread access to mental health services despite successful pilot interventions in the province of Nangarhar [4, 43, 44] and the integration and recent scaling up of psychosocial models of handling into the basic package of health services (health posts, wellness centers and district hospitals) [44–46]. Moreover, the prioritization of mental health support in customs-based interventions such as Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) [47, 48], has non translated into widespread effective mental health programs in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan beingness delievered through the CBR platform. The persistent low utilization of healthcare services by persons with mental disorders represents a dynamic problem (Fig. 1) that challenges both policy makers and program implementers.

Reference mode: Rate of service utilization by people with mental disorders

Community based system dynamics (CBSD) represents a novel approach that holds promise for problem assay and policy blueprint. Similar other participatory approaches such as Theory of Alter (ToC) or Participatory Action Research (PAR) used to address public health problems [49–51], CBSD engages stakeholders who are embedded in a system to examine complex problems [52]. CBSD highlights the feedback within systems, and examines dynamic change in system beliefs over time, as well as nonlinear relationships, allowing for explicit appointment with causal mechanisms in complex issues. CBSD provides a structured process and forum for diverse stakeholders to identify issues and prioritize intervention through the language of systems, and to support the development of stakeholders' chapters to engage with practical problem-solving [20, 53].

In the nowadays study, nosotros study on a CBSD-informed Group Model Edifice (GMB) workshop to consider how an Afghan customs based rehabilitation plan might effectively expand its interventions to cover the needs of people with mental affliction.

This paper examines the dynamics of mental health service seeking and capacity for supporting people with mental affliction from the perspective of a CBR program operating in Afghanistan. It proposes insights into ways to enhance access to mental health services for people with mental disease (PMI).

Methods

Setting

The report was carried out with staff of a CBR program providing services for persons with disabilities in 13 provinces of Northeastern Afghanistan.

Study design and participants

We initiated a series of Group Model Building sessions with Community-Based Rehabilitation workers (CBRW) and CBR team leaders from a large international organization operating in the northern and eastern regions of Afghanistan. The purpose of the sessions was to investigate questions arising from initial findings of a 3-year impact evaluation enquiry report. Initial GMB sessions were held over in June 2014 in Mazar-e-Sharif, Balkh, Afghanistan, and follow-upwards sessions were conducted in Kabul, Afghanistan in February 2015. The initial sessions were conducted with three males and iii females customs based rehabilitation workers from the Mazar-e-Sharif region. Sessions were also conducted with four males CBR workers from Jalalabad to triangulate findings of the first sessions. The follow-up sessions consisted of 2 male and two female person research officers with experience in both CBR and research methods (Table ane). These four participants in the follow-up sessions were from Mazar-eastward-Sharif, Taloqan, Ghazni and Jalalabad, four regional program offices of our partner NGO.

Sessions were planned based on a series of scripts adapted from Scriptapedia a manual composed of structured group model edifice activities [54], and were led by a team consisting of Afghan NGO staff members and of three international researchers as facilitators. Sessions included a series of scripts (Table two) designed to explore the interactions and interdependencies between factors affecting participation of people with severe and disabling forms of mental disorder in CBR activities, and to develop a common model of the complex local dynamics and explore possibilities for intervention to provide care to PMI. In detail, session particpants described the existing relational dynamics among the set of factors identified by constructing causal loop diagrams (CLDs).

Analysis

Preliminary analysis occured during the procedure of elaborating and refining these graphical models, or "causal loop diagrams". CLD elaboration activities and model review activities, described in Tabular array 1, provided an opportunity to assess the structure of the model for face validity and to derive insights about how session participants understood the structure of the trouble. These discussions and group insights were documented by members of the facilitation team through handwritten notes and reflected via revisions to the model. Throughout the form of the sessions, this group assay drove the development of multiple iterations of the model, all of which were documented through photographs and notes.

The session was initiated with an practise to develop a mutual perspective of mental disorders to come to a shared understanding of the key concept of mental illness (Table 1). Findings illustrate the complexity of defining psychiatric and psychological disorders as well as learning disability in Dari and Pashto – two main languages used in Afghanistan - as also shown past previous piece of work done in Afghanistan effectually mental health [55–58]. Dari and Pashto practise not accept clearly specified terms for mental disease. Session participants referred to: (i) Dewana which is a pejorative term, meaning "mad" or "crazy" with strong stigma associated to it; and (ii) Rawani which is a broad concept which includes mental illness and intellectual inability, and can commonly be described as "someone who acts like they are young". I participant described the differences in mutual usage bluntly: "Diwana is always a trouble. The person causes problem. She is non considered as normal, at that place is no way her condition tin can amend". Other terms referring to mental distress and anxiety such as "asabi" signifiying "nervousness" and "agitation" were briefly discussed as well. Previous discussions with organizational leadership and CBR workers in the context of preparation sessions revealed pregnant variation in private conceptions of what qualifies every bit mental illness. Participants came to a common approximation of the English term for mental affliction, termed every bit "Rawani" but specifying a focus on 'astringent psychological bug' and drawing a distinction betwixt intellectual and mental disability. The specification of terms inside the modeling session allowed us to develop a model of a circuitous concept that did not have a articulate Dari or Pashto language analog.

Betwixt sessions and afterwards the conclusion of the workshop, the researchers iterated a farther serial of revised model using Vensim PLE software. Revisions primarily focused on closing implicit feedback loops and taking decisions nigh how constructs could exist aggregated or disaggregated to clarify meaning. All revisions were grounded in the model itself and based on notes taken by the facilitation team during the GMB session.

To examine the contributions of CBSD to an overall understanding of the dynamics of support for better access to mental healthcare for PMI, we used a framework of Levels of Customs-level System Insights, proposed by Hovmand [52]. This framework provides a lens through which to understand the types of system insights gained through model building activities, from surface level descriptions of the organisation to deep insights virtually the causes of organisation behavior.

Results

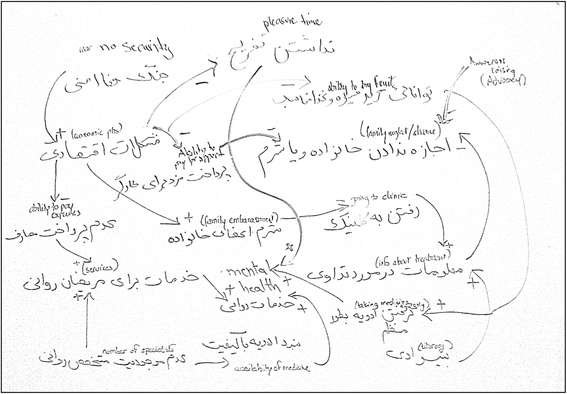

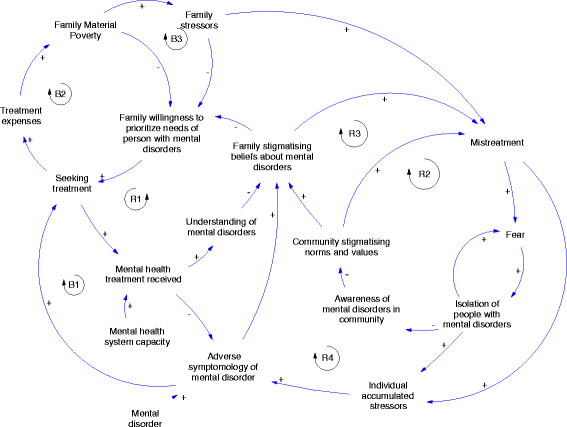

The product of the different GMB sessions was a serial of causal loop diagrams that document the evolving vision of the complex challenge of providing mental health services for people with mental affliction. Figure 2 presents the preliminary CLD produced at the end of session ane, and Fig. iii presents the revised CLD.

Example of a Causal Loop Diagram for exploring barriers and facilitators of service seeking for persons with mental disorders

Final Causal Loop Diagram

Causal loop diagrams (CLDs) can be read using a few key principles. Arrows, or links, correspond causal relationships. The plus and minus symbols of the model indicate the polarity, or the direction of the causal relationship. The plus sign indicates a relationship that goes in the aforementioned direction, a minus sign represents an changed relationship. For example as a family'south material poverty increases, this causes a commensurate increase in stressors on the family unit. The inverse is also true: if a family's material poverty reduces, that reduces family unit stressors. This is a positive relationship. The human relationship betwixt family unit stressors and family unit willingness to prioritize the needs of persons with mental disorders in Fig. iii represents an inverse relationship. As family stressors increment, this causes a subtract in families' willingness and ability to prioritize the healthcare and other needs of a family unit member with mental disorders. The opposite of grade is true. Equally family unit stressors decrease, they have more than capacity and willingness to prioritize the needs of a family member with mental disorders.

The revised model in Fig. three contains multiple interacting feedback loops. Tabular array two summarizes the major feedback loops that institute a hypothesis of how system components interact to generate a persistently low rate of service utilization by people with mental disorders.

The beginning balancing loop (B1) shows in Tabular array iii that if persons with mental illness seek more treatment, adverse symptoms might be reduced, encouraging them to seek more treatment and show more medical compliance. (B2) displays the brutal bike between poverty and mental disorders: people are poor and cannot beget to spend fifty-fifty small amount on medical care for the PMI, making the situation of scarcity of mental care within the BPHS (supposedly gratis) even more daring for those families. (B3) links this relationship between treatment needs associated with mental disease and poverty to the stressors caused by the risk of falling deeper into poverty if the family has to spend resource for the medical needs of the PMI.

The four reinforcing feedback loop demonstrate the many ways in which public stigma impacts the wellbeing of PMI. (R1) indicates that as understanding of mental illness becomes more common, families' stigmatizing beliefs about mental illness lessen. Again the inverse is true. Every bit understanding is reduced, stigmatizing beliefs increase. The second reinforcing loop illustrates a worrying effect of stigma: mistreatment of PMI. As norms and values reverberate increasingly prejudice and discrimination of PMI, likelihood of them being mistreated raises, resulting in fear and isolation from the community to preclude mistreatment. The 3rd reinforcing loop shows that every bit stigmatizing norms and values are more than prevalent amid the community, so are stigmatizing beliefs about mental illness. The opposite is true; as community stigmatizing norms decrease family stigmatizing beliefs as well decrease. Finally, (R4) shows how stigma, by fueling practices of diverse forms of mistreatment (use of bad language and bullying, harassment, physical violence), has a negative effect of the mental state of the PMI which in turn influences negatively beliefs and behaviors towards PMI.

At the close of the sessions the facilitators initiated a discussion about possible leverage points to change the current dynamic and introduce interventions in the existing organization to better access to mental healthcare for PMI.

One participant argued, "the easiest intervention is awareness with a lot of positive outcomes. If CBR workers inform people through home training and community based sensitization intervention, this can reduce existing fearfulness. We probably need more psychologists to train our CBR workers and scale upwardly our awareness program. And the EPHS/BPHS arrangement lacks resources to pay those professionals as well." Another participant added: "CBR workers tin can address persons with mental affliction (rawani) to health clinics or hospitals inside the BPHS and EPHS. It is an of import role because they are the only one doing outreach to families". Another i mentioned that the family is the first identify to deport out awareness and sensitization: "If the family unit does non accept the mental affliction how tin the wider community accept it?". Participants agree that awareness can have leverage on different aspects of the problems. "Once we identify a person with mental illness, we can approach the family, induce some positive behaviors such as avoiding naming the person dewana, promoting participation in family activities, interest in ceremonies and encourage interaction with the community". "If we manage to reduce such behaviors, we definitely improve the wellbeing of the person and her family. […] In other words, more acceptance, more happiness". "If a community is aware of the upshot of mental illness, then she can as well lobby the government to provide services. If the government is pressured to arbitrate, it volition pledge resource to hire psychologist in healthcare facilities that in turn will be able to acquit training for CBR and health workers that go in the communities to identify persons with mental illness. This model exists for midwife which requires a 2 years training. Simply obviously this has a cost and maybe we will have to start modestly with brusque term trainings". Another added: "If we explain to the family unit that the condition tin improve, and then the family will be encouraged to seek for treatment. In Mazar for instance, we accept 2 or 3 specialized doctors. If the family is not sensitized to mental illness, and the CBR worker asked them to consult one of these psychiatrists, the family volition non accept the person with mental disease because she is afraid of people saying she is dewana. People are difficult to convince but the outset step is irresolute attitudes". Another one mentioned: "the causal loop diagram shows a articulate path for CBR intervention. CBR workers can work with the community to reduce stigma. Working in the community, they have a privileged access to Mullahs, teachers and elders (Shurah or village assembly members) that they can influence and convince to spread a message of inclusion and tolerance".

Give-and-take

The CBSD model developed collaboratively between CBR workers and team leaders and researchers provides insight into the factors that impede admission to mental healthcare for persons with mental illness and what intervention could be done to change the status quo. CBSD establishes the causal loop relationships that explain poor access to mental healthcare and identifies points of leverage for intervention. Because the points for intervention were identified by people directly involved with the trouble with support from experts facilitating the process of identification, the stakeholders may be amend motivated to implement the solutions they establish. In fact, our approach shares with ToC the aim of exploring solutions to complex issues using a participatory approach and ensuring stakeholders buy-in and sense of ownership [59]. In both approaches, solutions to address the problem have into business relationship the context, in detail existing needs, difficulties such every bit power relations, barriers to intervention and possible remedies to problems [60]. Withal, the CBSD approach differs from a ToC approach in the method used. The ToC works backward from defining in partnership the intended bear on – e.1000. better admission to care, to determine required intermediate and short-term outcomes to attain the aim, and the related indicators associated with each outcome [59, 61]. Furthermore, the CBSD approach does not presume ex ante the adoption of whatever component of a mental wellness care package as in the instance of the Programme for Implementing Mental Health Care (Prime number) programme using a ToC approach [8] simply engage stakeholders and let them make up one's mind first the organisation and its components and identify leverage points for intervention. Every bit a result, the CBSD approach is a tool that tin can be used earlier a ToC is elaborated. The CBSD approach gives a voice to stakeholders who tin can share their views of a problem, come upward with solutions nearly what could be done to address them, elements that can exist embedded in a ToC.

Components of the system

Surface level system insights that emerge from the model include the limerick and interaction betwixt individual, family unit, and community level variables. The model describes the broad connections betwixt family economic situations, mental healthcare seeking, and mistreatment in the community and family. The telescopic of these components represents a vision of care-seeking that is centered on family conclusion making and is contingent upon both the availability of such healthcare and the social and economic environment of the family. A dynamic hypothesis that emerges from this model is that the interaction of economic burdens of generalized poverty and handling expenses interact with cultural and social stigmatizing behavior, in the context of limited clinical or other treatment support, to perpetuate low admission of any form of intendance for people with mental illness. This interaction of feedback loops describes a state of affairs in which, even if clinical mental healthcare capacity were to be introduced, community stigma and economic forces would still correspond pregnant barriers to admission. This simple visual representation connects a number of important insights that have been shown separately by unlike studies: limited resources are bachelor for mental healthcare services in Afghanistan despite original initiatives [iv, 43, 44], that poverty plays a function in discouraging mental healthcare seeking behaviors [62] and the importance of stigma associated to mental affliction [57].

As important as the content of the model are the concepts that are highlighted and left out by the participants in the session, in other words how members of a organization think near their arrangement. Specifically, participants operated with an understanding that mental illness is something that is acquired by outside or unknown forces. There is an additional assumption that mental illness is treatable through clinical support, shown by the link that treatment received reduces agin symptomology. Implicit in this mental health treatment variable is a vision of treatment that is primarily psychiatric. There was piffling discussion of any form of psychosocial counseling as a response to mental illness or its symptoms. Additionally, the assumptions of the model were that treatment primarily occurred through formal clinical mechanisms, though at that place was discussion of a function for trained outreach workers. This perspective suggests that whatever intervention associating medical treatment and psychosocial services will require data and sensitization of non-specialist health and rehabilitation workers to become their buy-in and participation.

Points of entry for intervention

Finally, the model reveals a number of potential entry points for programmatic or community intervention to address depression service receipt by PMI. Participants mentioned awareness of families and communities of the needs and rights of PMI as a potential leverage point. They argued that CBR workers are already experienced in reaching out to the community in villages where the CBR program is taking place through sensitization campaigns to promote acceptance and change attitudes towards people with disabilities generally. A sensitization effort to achieve out to families (the "Understanding of mental disorders" variable) and communities ("Awareness of mental disorders in community") would potentially have significant bear upon on the adverse symptomology of mental disease through reductions in stigma and in mistreatment, as well as through increased willingness to support treatment seeking for affected family members. Participants in the model building sessions discussed that such sensitization programs could work through multiple avenues: through direct face-to-face outreach with families of PMI; sessions with organizations of persons with disabilities (DPOs); and participating in community events within schools, mosques and during sessions of village shuras (committees of elders) meetings. Similarly, studies using a ToC approach identified the need for mental health sensation raising and engaging with PMI and their families equally important activities in other low-income contexts [63].

Other points of programmatic entry into this system were identified equally potentially valuable, just not strictly within the purview of the CBR Program. Investments in developing the chapters of the mental healthcare system through the development of new preparation expertise within Afghanistan for psychiatrists, psychologists, and potentially social workers could be some other avenue for NGO involvement. Such intervention has been pioneered by Healthnet TPO in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan [four]. Other studies take shown elsewhere the demand for specialized mental health professionals to drive the procedure of developing and integrating mental healthcare as part of the primary healthcare organisation [64, 65]. Finally, promotion of family livelihood strategies would bear upon the overall family context, which is argued to accept a central, if indirect role in the experience and support of PMI. This finding reinforces emerging literature demonstrating the association that exists between poverty, stigma and mental illness in low-income countries [66].

Limitations

Our study is the commencement instance of the apply of community based system dynamics looking at mental illness in a conflict setting. Considering of the new context, multiple challenges in the design and facilitation of the sessions had to be addressed, which are reported here. 1 of the strengths of this approach is the ability to make explicit the subjectivities of individuals who are edifice the model. This perspective of participants who are embedded in the system allows for insights into interconnections and dependencies that may not be apparent from an external view. This strength also argues for caution: this subjectivity comes with biases and limitations of knowledge that may challenge the validity of findings. As the sessions were intended to be a rapid exploration of the initial findings of the bear on evaluation study, the scope of the study was limited to participation past CBR workers. Without the voices of people with mental disease included in the study, there are clear biases in the understanding of mental illness. For example, discussions of mental wellness treatment were primarily focused on a vision of treatment that is primarily psychiatric. In that location was niggling give-and-take of whatsoever form of psychosocial counseling as a response to severe mental disorders or its symptoms. The choice to include merely CBR workers was based on both logistical feasibility as well as concern for the appropriateness of engaging vulnerable stakeholders in an exploratory written report. Further extension of the method to include people with mental illness would be a logical and desirable next footstep, merely would require significant consideration of the framing of the approach and composition of facilitation squad. Additionally, generalizing findings to whole organization based on the vision of a few stakeholders may jeopardize validity. Replication and triangulation through multiple sessions with diverse stakeholder groups would exist necessary to strengthen findings. The co-development of a model represents a deeper level of engagement with the problem than conventional qualitative research methods such every bit focus groups, yet, convergence of opinions by participants in a system model does not necessarily interpret to intention or capacity for action. As with any participatory method, the CBSD approach requires involvement of organizational leadership to implement findings and recommendations. Finally, the role of the outside facilitators cannot be ignored. The identification of the problem in this study stems from the results of a partnership with academic researchers who accept feel in an Afghan context. The resulting model is a negotiation betwixt facilitators' prompts and participants' understandings and perspectives. Neither would achieve the outcomes on its own.

Implications

Our study demonstrates that CBSD methods can provide an effective tool to elicit a common vision on the complex/messy problem of access to care for PMI and identify shared potential strategies for intervention in line with the goals of the WHO's Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 [67]. The procedure and the resulting model showed that: (i) a multiple stakeholder groups can clarify complex causal loops that impede access to intendance for PMI and provide ideas for intervention; (two) a successful facilitation procedure preserves the vision and perspectives of participants while reaching a mutual agreement of unmet mental healthcare needs; (three) a roadmap to intervention shared by various stakeholders involved in the program tin can be delineated with express input of expert knowledge.

The effect of lack of access to mental health services in low-income countries is the field of study of growing research and literature specially around the demand of constructive interventions in context of express financial and professional resources [68–70]. An important issue that remains to exist adequately addressed is the role of stigma as a strong driver of discrimination of PMI resulting in exclusion from treatment but likewise from employment and community participation [66]. Such a process of exclusion results in poor self-esteem and internalized stigma, fabric poverty for the person and her family and deepening and mental suffering as underlined by CBSD participants [71, 72]. These dynamics articulated in the literature were elaborated over the course of only a few sessions through the complex interactions of feedback loops. They suggested that an appropriate strategy must address community and families' perception of mental disorders to reduce stigma and barriers to seeking outside support. Participants identified the atmospheric condition for expanding the current programme to address the needs of PMI: revising organizational priorities, building staff expertise and increasing in-country grooming chapters in psychiatry and psychology. Our study demonstrates that the CBSD modeling process can elicit these relationships with minimal expert input. This suggest that endogenous expertise – i.due east. knowledge of the people involved in the system itself – may exist acceptable to frame a sophisticated statement about the messy problem of CBR access for people with mental illness.

Conclusion

In a context of limited resources, the CBSD arroyo suggests a unlike path for program planning and eventually evaluation. The originality of the trouble solving approach described in our study is that it is driven by people embedded within the system. It can generate robust sophisticated results with actionable policy recommendations building on the knowledge and expertise of participants.

This approach offers a new collaboration framework that privileges the knowledge of people involved in the arrangement and focuses on outcomes that address the needs of communities. The procedure of community based system dynamics tin provide a window for organizational reflection and the opportunity to build a common vision and momentum for action. This is specially valuable for messy and neglected problems such equally mental illness for which needs for intervention are all the same considerable in low-income settings.

Abbreviations

CBR, community based rehabilitation; CBRW, community-based rehabilitation worker; CBSD, customs-based system dynamics; CLD, causal loop diagram; DPO, Disabled Persons Organization; GMB, Group Model Building; NGO, Not Governmental Organization

References

-

Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;iii(2):171–8.

-

Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, et al. The Global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011.

-

Earth Health Organization. Building dorsum better: Sustainable mental wellness intendance after emergencies. Geneva: World Health System; 2013.

-

Ventevogel P, van de Put W, Faiz H, van Mierlo B, Siddiqi M, Komproe IH. Improving access to mental wellness care and psychosocial support within a delicate context: A case study from Transitional islamic state of afghanistan. Plos Med. 2012;9(v):e1001225.

-

Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee South, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and centre-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370(9591):991–1005.

-

Shidhaye R, Shrivastava S, Murhar Five, Samudre S, Ahuja S, Ramaswamy R, et al. Development and piloting of a program for integrating mental health in primary intendance in Sehore district, Madhya Pradesh, Bharat. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208:s13–20.

-

Gureje O, Abdulmalik J, Kola L, Musa Due east, Yasamy MT, Adebayo K. Integrating mental health into chief care in Nigeria: Report of a demonstration project using the mental health gap action plan intervention guide. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;xv(1):242.

-

Lund C, Tomlinson Chiliad, de Silva G, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, et al. PRIME: A Programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low- and middle-income countries. Plos Med. 2012;ix(12):e1001359.

-

Lund C, Alem A, Schneider M, Hanlon C, Ahrens J, Bandawe C, et al. Generating testify to narrow the treatment gap for mental disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: Rationale, overview and methods of AFFIRM. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(iii):233–twoscore.

-

Semrau Grand, Evans-Lacko S, Alem A, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chisholm D, Gureje O, et al. Strengthening mental wellness systems in low- and middle-income countries: The Emerald programme. BMC Med. 2015;xiii(1):79.

-

Patel V, Saxena S. Transforming lives, enhancing communities - Innovations in global mental wellness. North Engl J Med. 2014;370(6):498–501.

-

Kim MM, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Bradford DW, Mustillo SA, Elbogen EB. Healthcare barriers amongst severely mentally ill homeless adults: Show from the five-site wellness and risk study. Adm Policy Ment Wellness Ment Health Serv Res. 2007;34(4):363–75.

-

Rebello TJ, Marques A, Gureje O, Motorway KM. Innovative strategies for closing the mental health handling gap globally. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(4):308–14.

-

Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1164–74.

-

Ssebunnya J, Kigozi F, Kizza D, Ndyanabangi S. Integration of mental health into principal wellness care in a rural district in Republic of uganda. Afr J Psychiatry (Southward Africa). 2010;thirteen(ii):128–31.

-

Trani JF, Barbou-des-Courieres C. Measuring equity in disability and healthcare utilization in Afghanistan. Med Confl Surviv. 2012;28(3):219–46.

-

Trani J-F, Bakhshi P, Noor AA, Lopez D, Mashkoor A. Poverty, vulnerability, and provision of healthcare in Afghanistan. Soc Sci Med. 2010;seventy(11):1745–55.

-

Chocolate-brown VA, Harris JA, Russell JY. Tackling wicked problems through the transdisciplinary imagination. London: Earthscan; 2010.

-

Kreuter MW, De Rosa C, Howze EH, Baldwin GT. Understanding wicked issues: a key to advancing ecology health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(4):441–54.

-

Vennix JA. Group model-building: tackling messy issues. Syst Dyn Rev. 1999;15(4):379–401.

-

Kreuter MW, Hovmand P, Pfeiffer DJ, Fairchild M, Rath S, Golla B, et al. The "Long Tail" and public health: new thinking for addressing health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2271–eight.

-

Lake A. Early babyhood evolution-global action is overdue. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1277–8.

-

Kabeer N. Gendered poverty traps: Inequality and care in a globalised world. Eur J Dev Res. 2011;23(4):527–30.

-

Kabeer Due north. Between affiliation and autonomy: Navigating pathways of women'south empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Dev Chang. 2011;42(2):499–528.

-

Kabeer North. Women'due south empowerment, development interventions and the direction of information flows. Ids Bull-Institute Dev Stud. 2010;41(6):105–thirteen.

-

Chambers R. 'Who counts? The quiet revolution of participation and numbers'. 2007.

-

Minkler 1000, Wallerstein N. Customs-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken; 2011.

-

Cooke B, Kothari U, editors. Participation: the new tyranny? London: Zed Books; 2004.

-

Williams G. Evaluating participatory development: tyranny, ability and (re) politicisation. Tertiary World Q. 2004;25(iii):557–78.

-

Sen AK. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press; 1999.

-

Earth Health Organization. Mental health and development: targeting people with mental health conditions equally a vulnerable group. 2010.

-

Patel V, Jenkins R, Lund C. Putting show into practice: the plos medicine serial on global mental health exercise. Plos Med. 2012;9(v):e1001226.

-

Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS. M challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475(7354):27–30.

-

Patel V, Boyce Due north, Collins PY, Saxena South, Horton R. A renewed agenda for global mental health. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1441–ii.

-

Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of affliction owing to mental and substance apply disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86.

-

Littlewood R. Cultural variation in the stigmatisation of mental illness. Lancet. 1998;352(9133):1056–7.

-

Jacob M, Patel V. Classification of mental disorders: a global mental wellness perspective. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1433–5.

-

Mascayano F, Armijo JE, Yang LH. Addressing stigma relating to mental illness in low-and heart-income countries. Front end Psychiatry. 2015;6:38.

-

Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, Busch JT. Intervening inside and across levels: A multilevel arroyo to stigma and public wellness. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:101–9.

-

Lopes Cardozo B, Bilukha OO, Gotway Crawford CA, Shaikh I, Wolfe MI, Gerber ML, et al. Mental wellness, social functioning, and disability in postwar Afghanistan. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292(five):575–84.

-

Miller Thou, Omidian P, Rasmussen A, Yaqubi A, Daudzi H. Daily stressors, war experiences, and mental health in Afghanistan. Transcult Psychiatry. 2008;45(4):611–39.

-

Panter-Brick C, Eggerman Yard, Gonzalez V, Safdar S. Violence, suffering, and mental health in Afghanistan: a schoolhouse-based survey. Lancet. 2009;374(9692):807–16.

-

Ventevogel P. Mental wellness and primary care: Fighting against the marginalisation of people with mental health problems in Nangarhar province, Afghanistan. In: Trani JF, editor. Development efforts in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan: is in that location a will and a mode? The case of disability and vulnerability. Ethique economique. Paris: L'Harmattan; 2011. p. 215–42.

-

Epping-Jordan JAE, van Ommeren M, Ashour HN, Maramis A, Marini A, Mohanraj A, et al. Across the crisis: Building dorsum amend mental wellness care in 10 emergency-affected areas using a longer-term perspective. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2015;9(1):fifteen.

-

Ayoughi S, Missmahl I, Weierstall R, Elbert T. Provision of mental health services in resource-poor settings: A randomised trial comparing counselling with routine medical handling in Due north Afghanistan (Mazar-eastward-Sharif). BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:14.

-

Ministry of Public Health. A basic package of wellness services for Afghanistan, 2005/1384. Kabul: Ministry of Public Health; 2005.

-

Raja S, Boyce WF, Ramani S, Underhill C. Success indicators for integrating mental health interventions with community-based rehabilitation projects. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008;31(4):284–92.

-

World Health Organization. Customs-based rehabilitation: CBR Guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

-

De Silva MJ, Breuer Due east, Lee L, Asher 50, Chowdhary N, Lund C, et al. Theory of change: a theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Quango's framework for circuitous interventions. Trials. 2014;15(1):267.

-

Osrin D, Mesko North, Shrestha BP, Shrestha D, Tamang S, Thapa Due south, et al. Reducing childhood bloodshed in poor countries - Implementing a customs-based participatory intervention to improve essential newborn care in rural Nepal. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97(1):xviii–21.

-

Minkler Yard. Using participatory activeness research to build good for you communities. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(2-3):191–7.

-

Hovmand PS. Customs based organization dynamics. New York: Springer; 2014.

-

Rouwette EA, Korzilius H, Vennix JA, Jacobs Eastward. Modeling as persuasion: the touch on of group model building on attitudes and behavior. Syst Dyn Rev. 2011;27(one):i–21.

-

Hovmand PS, Rouwette EAJA, Andersen DF, Richardson GP, Kraus A. Scriptapedia iv.0.6. 2013.

-

Ventevogel P, De Vries G, Scholte WF, Shinwari NR, Faiz H, Nassery R, et al. Backdrop of the Hopkins symptom checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-twenty) as screening instruments used in main intendance in Afghanistan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(iv):328–35.

-

Miller K, Omidian P, Quraishy A, Quraishy N, Nasiry Yard, Nasiry S, et al. The Afghan symptom checklist: a culturally grounded approach to mental health assessment in a conflict zone. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:423–33.

-

Cerveau T. Deconstructing myths; facing reality. Understanding social representations of disability in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan. In: Trani JF, editor. Development efforts in Afghanistan: Is at that place a volition and a way? The case of disability and vulnerability. Ethique economique. Paris: L'Harmattan; 2011. p. 103–22.

-

Rasmussen A, Ventevogel P, Sancilio A, Eggerman Thousand, Panter-Brick C. Comparison the validity of the self reporting questionnaire and the Afghan symptom checklist: Dysphoria, aggression, and gender in transcultural assessment of mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):206.

-

Anderson AA. The community architect'south approach to theory of alter: A practical guide to theory evolution. New York: Aspen Establish Roundtable on Community Alter; 2006. p. 36.

-

Breuer E, De Silva MJ, Fekadu A, Luitel NP, Murhar V, Nakku J, et al. Using workshops to develop theories of alter in five low and middle income countries: Lessons from the programme for improving mental wellness care (PRIME). Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8(1):15.

-

Connell JP, Kubisch AC. Applying a theory of modify approach to the evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives: progress, prospects, and problems. In: Connell JP, Kubisch Air-conditioning, Schorr LB, Weiss CH, editors. New approaches to evaluating community initiatives. 2. Washington: Aspen Institute; 1998. p. 15–44.

-

Trani JF, Kuhlberg J, Cannings T, Dilbal C. Examining multidimensional poverty in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan: Who are the poorest of the poor? Oxford Evolution Studies. in press.

-

Hailemariam M, Fekadu A, Selamu M, Alem A, Medhin G, Giorgis TW, et al. Developing a mental wellness care plan in a low resource setting: The theory of modify approach. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2015;fifteen:429.

-

Patel V, Belkin GS, Chockalingam A, Cooper J, Saxena South, Unützer J. Grand challenges: Integrating mental health services into priority health care platforms. Plos Med. 2013;10(5):e1001448.

-

Hanlon C, Luitel NP, Kathree T, Murhar 5, Shrivasta Southward, Medhin Thou, et al. Challenges and opportunities for implementing integrated mental health care: A commune level situation analysis from 5 depression- and middle-income countries. Plos One. 2014;nine(2):e88437.

-

Ssebunnya J, Kigozi F, Lund C, Kizza D, Okello E. Stakeholder perceptions of mental health stigma and poverty in Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9(i):5.

-

World Health Arrangement. Comprehensive mental health activity plan 2013–2020. 2013. Geneva: Globe Wellness Organisation; 2013.

-

Barry MM, Clarke AM, Jenkins R, Patel Five. A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental wellness promotion interventions for immature people in depression and center income countries. BMC Public Health. 2013;xiii(i):835.

-

Cohen A, Eaton J, Radtke B, George C, Manuel BV, De Silva M, et al. Three models of community mental wellness services In depression-income countries. Int J Ment Wellness Syst. 2011;v:three.

-

Rahman A, Prince M. Mental health in the tropics. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103(2):95–110.

-

Pescosolido BA. The public stigma of mental illness: What practise we think; what do nosotros know; what can we evidence? J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(1):1–21.

-

Assefa D, Shibre T, Asher L, Fekadu A. Internalized stigma among patients with schizophrenia in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia: A cross-sectional facility-based report. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:239.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to admit the support of Swedish Committee for Afghanistan staff in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan in participating in the community based organisation dynamics sessions.

Authors' contributions

JFT, EB conceived of the paper, participated in the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. JFT, Lead and EB participated in the original pattern of the study, performed the original analysis and participated in the conceptualization of the paper. JFT and EB wrote a first draft of the newspaper. PH provided technical support. All authors read and approved the last manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cypher/1.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

Trani, JF., Ballard, East., Bakhshi, P. et al. Community based organization dynamic every bit an arroyo for understanding and acting on messy issues: a case study for global mental health intervention in Afghanistan. Confl Wellness 10, 25 (2016). https://doi.org/x.1186/s13031-016-0089-two

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s13031-016-0089-2

Keywords

- Afghanistan

- Causal loop diagram

- Customs based organisation dynamics

- Complex problems

- Development intervention

- Mental health

Source: https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-016-0089-2

0 Response to "Ballard Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Family Counseling Interventions"

Post a Comment